If you’ve ever gone to a class at the university level in the United States, it is likely you’ve been asked to fill out a “teacher evaluation” form. These are also given at many non-American universities too, just not all of them. Yet they are usually always going to involve a few evaluation questions.

Some of them might be how knowledgeable about the subject we felt our teacher was, how fast they responded to questions, what we thought the professor did well with/did not do well with, and often you’ll be given a section where you can make extra comments.

While these evaluations do not always affect if a professor keeps his or her job, a lot of universities overvalue the evaluation forms. Many professors miss out on getting tenure due to these forms, and on top of that, not every student in a course will fill them out.

Even if a professor offers an incentive to do so, there is no guarantee that students will do this. That can especially be tough to see for professors who teach an online course. The evaluations for teachers are not amended or altered for the online setting, which is often faster than an on-campus course.

One new study is calling out how evaluations are negatively affecting professors.

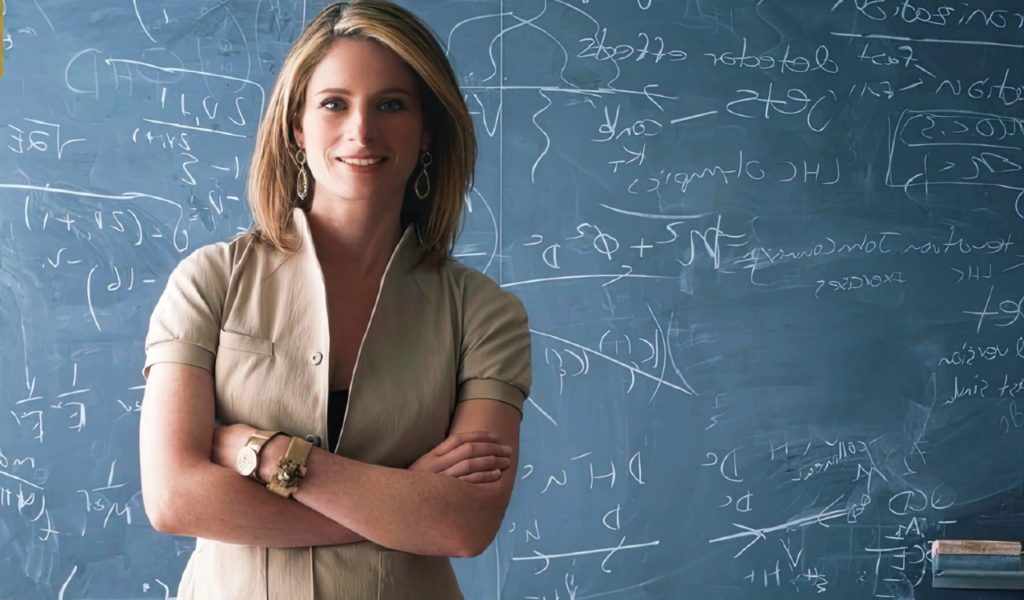

Evaluations Often Support Gender Biases

One new study finds that gender biases are playing a big role in whether or not an instructor remains employed. Teacher evaluations are often used to support the idea of removing an instructor, sometimes even if they are considered to be a relatively good teacher.

We should make a point here that we use the “gender” term on purpose. A person’s sex is biological but they can decide to identify as the opposite sex, possibly even at their workplace. As a result, a trans-female will be evaluated the same way as a biological female in this instance.

Factors unrelated to teaching performance, such as a person’s gender or race…even attractiveness, can skew how evaluations work out. Asking students to fill them out can lead to drastically different results, but universities put a lot of stock in them.

That is how a university might get away with firing a professor, even if they are good at their job. The university will claim bad performance via student evaluations. This way, a university does not have to come out and say they are firing a person for biases.

Study Results

The study found that being in the gender minority of your academic department can dramatically alter whether or not you’ll remain employed. As an example, in upper-level courses, women teaching in male-dominated departments tend to fare worse in their student evaluations.

The same principle actually occurs in the opposite situation, for males teaching in a female-dominated department. However, due to women being in the gender minority at most universities, the study finds that they are disproportionately affected.

Previous research suggested that in certain circumstances, individuals can actually be punished in their professional lives for defying the expectations of their specific gender. The study’s lead author, a Social Psychologist at the University of Cincinnati, Oriana Aragón, gave an example of this.

They referenced how in early childcare (usually dominated by women), men can experience negative bias in evaluations. The same holds true for women who take on a management role in a male-dominated field.

Yet to see if this type of bias existed at the university level, a lot of research needed to be done. This is why Aragón and their colleagues got to work on finding out just how problematic gender biases are in academia.

How The Study Was Conducted

Aragón and her team went through 100,000 evaluations from 4700 different courses at Clemson University. They found that if more men were in a department, women had lower average student evaluation ratings when teaching higher-level courses. The reverse also held true.

Yet in departments with roughly equal ratios of male and female professors, bias seemed to disappear entirely. Meanwhile, for lower-level courses, differences were not at all statistically significant.

Florida International University Social Psychologist, Asia Eaton, noted after seeing the results of the study: “The fact that women and men alike were penalized illustrates how stereotypes are broadly harmful. The studies in this paper do an excellent job of studying gender bias in context.”

However, the researchers were not done. They also showed students a website for a theoretical department with varying ratios of female and male faculty members. They could be found displayed in images on the faculty’s web page.

The researchers then gave the students a description of a mock course in the department, including a picture and biography of the male or female instructor for it. Students then filled out a teaching evaluation just like they would if they took the course.

In theoretically male-dominated departments, students rated female professors worse for upper-level courses and men for lower-level courses.

Things To Consider From The Study

It is clear that trying to get toward an even balance of male & female instructors for most departments would be ideal. It would likely ease biases in teaching evaluations. Until such an event occurs, men and women should be given the same achievement levels and both should teach lower & upper-level courses.

Some would also point out that we should not be putting such massive stock in teacher evaluations too. Others might disagree but this would be the best idea considering the biases have essentially been proven by this study. Yet some caution us to not overinterpret the results of this study.

Associate Dean for Teaching at Pennsylvania State University, Angela Linse, stated just that. She did commend the study for its large data set and novel experimental design but noted:

“Gender bias certainly exists, in both student and faculty populations. But the differences in ratings that the authors found—fractions of a point on a five-point scale—are not necessarily conclusive evidence of gender bias. Not all statistically significant differences are meaningful differences.”

Yet she still agreed that there are disparities in teaching evaluations. Thus, those should not make or break a professor’s professional career.